QUINTUS SEPTIMIUS FLORENS TERTULLINA

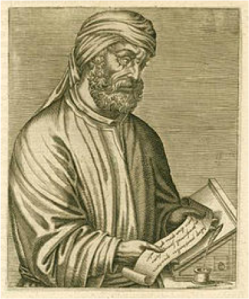

Very little is known about the life of the Christian apologist and writer Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullian except that which is found in his own writings and from other early historians such as Eusebious of Caesarea and Jerome. However, what can be clearly said and seen is that the prolific writings of Tertullian were instrumental in developing a rational, logical, and ardent defense against the many heresies of his day and have served to become the basis for Christian doctrine and what is now known to be orthodoxy. What will follow will be a brief look at the life or Tertullian through the eyes of church historians, both from the today and yesterday, and an examination of some of his most important writings in defense of Christians doctrine and orthodoxy.

Very little is known about the life of the Christian apologist and writer Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullian except that which is found in his own writings and from other early historians such as Eusebious of Caesarea and Jerome. However, what can be clearly said and seen is that the prolific writings of Tertullian were instrumental in developing a rational, logical, and ardent defense against the many heresies of his day and have served to become the basis for Christian doctrine and what is now known to be orthodoxy. What will follow will be a brief look at the life or Tertullian through the eyes of church historians, both from the today and yesterday, and an examination of some of his most important writings in defense of Christians doctrine and orthodoxy.

As mentioned above not much is known about the early life of Tertullian. What is generally agreed upon is that he was born in the Roman province of Carthage located in northern Africa around 155 CE. He was converted to Christianity in Rome around 190 CE but returned to Carthage where he became an influential leader and prolific writer. The facts around his childhood, his education, and profession seem to be grounded in church tradition stemming from the writing of his contemporaries and those that soon followed him.

Regarding his childhood . . .

Jerome (347-420 CE) writes the following, “Tertullian, the presbyter . . . was the son of a proconsul or Centurion.”[1] This paltry statement is one of very few statements that speaks to the childhood years of Tertullian and is seen by some modern day historians as suspect. For example, in Justo Gonzalez’s introduction to the early years of Tertullian the author’s language is vague and non-committal to the facts surrounding his early years and makes no mention of the possibility of his father being a Roman proconsul or Centurion. Additionally, according to literary critic Timothy David Barnes, Ph.d, “it is unclear whether any such position in the Roman military ever existed.”[2]

Jerome (347-420 CE) writes the following, “Tertullian, the presbyter . . . was the son of a proconsul or Centurion.”[1] This paltry statement is one of very few statements that speaks to the childhood years of Tertullian and is seen by some modern day historians as suspect. For example, in Justo Gonzalez’s introduction to the early years of Tertullian the author’s language is vague and non-committal to the facts surrounding his early years and makes no mention of the possibility of his father being a Roman proconsul or Centurion. Additionally, according to literary critic Timothy David Barnes, Ph.d, “it is unclear whether any such position in the Roman military ever existed.”[2]

Regarding his education and profession . . .

The common belief is that he was educated and trained in rhetoric and was most likely employed as a lawyer.[3] However this too has been called into question by critics such as Dr. Barnes who asserts that many of the writing that clearly identify Tertullian as a lawyer are only fragments and belong to a contemporary of Tertullian with the a similar name. Additionally Dr. Barnes asserts that the legal expertise exhibited in the writings of Tertullian is that which would be commonly known and understood by a Roman citizen.[4]

Regarding his writings and in particular marriage . . .

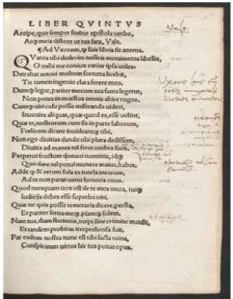

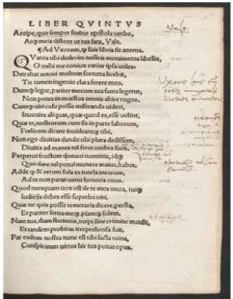

Despite the vagueness of Tertullian’s childhood and upbringing it is clear that he had a keen mind and an unyielding desire to define and defend Christian doctrine and orthodoxy. This is evidenced by his radical commitment to holiness as well as the many writings that are attributed to his name. These numerous writings cover a wide range of topics and issues that faced the early church and provide modern readers with a glimpse into how the early church viewed early practices and institutions. For example Gonzalez notes that Tertullina’s De Baptismo (On Baptism) is the oldest surviving work that speaks to the early church’s view and practice of baptism and that his two letters Ad Uxorem (To His Wife) provide a glimpse into how the early church viewed marriage marriage.[5]

Ad Uxorem Tertullian make many observations regarding marriage that many would find to be still held in the modern day Evangelical Christian Church. First, that although marriage is good and lawful, he views celibacy as being preferable. For example he writes the following,

Ad Uxorem Tertullian make many observations regarding marriage that many would find to be still held in the modern day Evangelical Christian Church. First, that although marriage is good and lawful, he views celibacy as being preferable. For example he writes the following,

In short, there is no place at all where we read that nuptials are prohibited; of course on the ground that they are “a good thing.” What, however, is better than this “good,” we learn from the apostle, who permits marrying indeed, but prefers abstinence; the former on account of the insidiousnesses of temptations, the latter on account of he straits of the times.[6]

Other views held by Tertullian that are still held by many today is that there will be no marriage in the resurrection, marriage is lawful but polygamy is not, marriage serves to sooth the flesh of its carnal desires, it provides the legitimate avenue for the blessing of children, and that death definitely ends the marriage covenant and returns freedom to the surviving spouse. However it is on this last observation that some modern day evangelicals might find some disagreement.

For Tertullian the motive of all Christian men and women was to live a life in pursuit of the highest good, the truest truth, holiness, and as noted above although it was good to be married it was better and more preferable to be single and celibate. Therefore, in his view, once liberty and the freedom to worship God without distraction had been returned through the death of a spouse the surviving spouse should seek to devote himself or herself to the ministry of the church. This view is not emphasized or held by many today. In fact it is common practice, and almost expected, that those who find themselves newly single will eventually remarry.

Regarding the rigorousness of Tertullian . . .

Tertullian’s rigorous pursuit of truth and of the highest good not only shaped his view of marriage but also led to his eventual break from the church and his involvement with Montanism.

Montanism was an extreme sect of early Christianity that believed that the true church had entered into a new age marked by the prophecies of Montanus who called for a more rigorous life. The attraction for Tertullian is clear as he struggled with his own sins and those of other believers. For him Montansim provided a means of explaining why sin existed in the life of the believer even after baptism as well as provided a system of dealing with those sins. Still the rigorous lifestyle of Montansim proved to be insufficient and eventually he left this order and formed his own sect, which would later be known at the Tertullinaists.[7]

It is an interesting fact that whereas the Roman Catholic Church has canonized many of his contemporaries as Saints, Tertullian’s involvement with Montanism and the formation of his own sect based on the rigors of his own writings has prevented the Roman Catholic Church from labeling him as a Saint.

Regarding Adversus Praxean (Against Praxeas) . . .

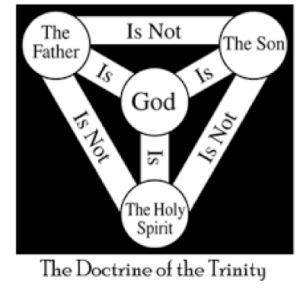

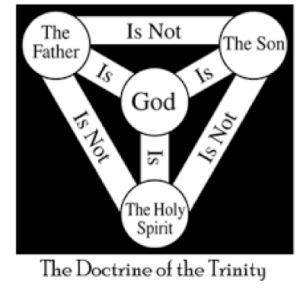

The most compelling argument for Tertullian’s contribution to Christendom is his early work in the formation of the Trinitarian view of God as a defense against the heresies of Praxeas and what would come to be know as patripassianism.[8] Tertullian writes the following against Praxeas;

That this rule of faith has come down to us from the beginning of the gospel, even before any of the older heretics, much more before Praxeas . . . especially in the case of this heresy, which supposes itself to possess the pure truth, in thinking that one cannot believe in One Only God in any other way than by saying that the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost are the very selfsame Person.[9]

In this seminal defense of the faith Tertullian is the first to develop the following view of God, which would serve as the foundation for the Doctrine of the Trinity, “one substance and three persons.”

For Tertullian, the paradox and mystery of God, was not something to be fully understood but that did not mean that humankind could not grasp the truth of the Trinity for God himself had revealed himself in the following ways. First, there eternally existed God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Ghost. Secondly, these three are not distinct gods but one God of the same substance. Finally, although they are distinct in person, or aspect, or power, they again are of one substance and fall under the names of the Father, and of the son, and of the Holy Ghost. Again Tertullian writes;

For Tertullian, the paradox and mystery of God, was not something to be fully understood but that did not mean that humankind could not grasp the truth of the Trinity for God himself had revealed himself in the following ways. First, there eternally existed God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Ghost. Secondly, these three are not distinct gods but one God of the same substance. Finally, although they are distinct in person, or aspect, or power, they again are of one substance and fall under the names of the Father, and of the son, and of the Holy Ghost. Again Tertullian writes;

As if in this way also one were not All, in that All are of One, by unity (that is) of substance; while the mystery of the dispensation is still guarded, which distributes the Unity into a Trinity, placing in their order the three Persons-the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost: three, however, not in condition, but in degree; not in substance, but in form; not in power, but in aspect; yet of one substance, and of one condition, and of one power, inasmuch as He is one God, from whom these degrees and forms and aspects are reckoned, under the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. How they are susceptible of number without division, will be shown as our treatise proceeds.[10]

Throughout this work the keen legal mind of Tertullian and his expertise in the tools of rhetoric are clearly displayed as he defends and defines the doctrine that would formerly become know as The Doctrine of the Trinity. In fact Tertullian is the first writer to use the word Trinity and is also the first to begin to define the terms substance and economy that are the foundational elements of understanding how as he observes a Unity can be divided into diversity.

Concluding thoughts . . .

Anyone seeking to understand the mode and thinking of early Christianity as well as the modern views of Christian doctrine would be well served to read and study the writings of Tertullian.

In them they will find the work of a brilliant mind that was dedicated to defining and defending the beginning of the Christian faith through thoughtful and logical argument and understanding. In addition to this the reader will gain an appreciation for not only the past but also for today as many of the topics that modern day skeptics struggle with are the very same notions that skeptics of yester-year struggled with. The doctrine of the Trinitarian God was a mystery then and is still a mystery today.

By having an appreciation for and understanding of the foundational thoughts of Tertullian, believers today will be better equipped to explain the mysteries of God and perhaps remove many of the obstacles the prevent modern day skeptics from seeing Christianity as something more than a religion for the simple and unlearned, and begin to see it as it truly it – the one true path to the One True God.

– Steven Baker

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barnes, Timothy David. Tertullian: A Historical and Literary Study. 1985 edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Gonzalez, Justo L. The Story of Christianity. Rev. and updated, 2nd ed. New York: HarperOne, 2010.

SELECTED TRANSLATIONS

Excerpts from Tertullian’s Adversus Praxeam Chapter II provided by; http://www.tertullian.org/anf/anf03/anf03-43.htm#P10374_2906966

Experts from Tertullian’s Ad Uxorem provided by

http://www.tertullian.org/anf/anf04/anf04-11.htm#P700_173688

Excerpts from Jerome’s On Famous Men, Chapter 53 provided by; http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/2708.htm

SELECTED MEDIA

Image of Tertullian provided by; http://www.higherpraise.com/preachers/tertullian.htm

Image of Ad Uxorem provided by; https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/item/NZD5G7XB5WFLME6VRPV4L3GC7Y3SV7UP

Map of Mediterranean Sea and Christian Area; http://www.higherpraise.com/preachers/tertullian.htm

[1] Translation of Jerome’s On Famous Men, Chapter 53 provided by; http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/2708.htm

[2] Timothy David Barnes, Tertullian: A Historical and Literary Study, 1985 edition. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), 11.

[3] Justo L. Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, Rev. and updated, 2nd ed. (New York: HarperOne, 2010), Location 1715 of 9758.

[4] Barnes, Tertullian, 23–27.

[5] Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, 1699=1715 or 9758.

[6] Experts from Tertullian’s Ad Uxorem provided by; http://www.tertullian.org/anf/anf04/anf04-11.htm#P700_173688

[7] Ibid., 1780 or 9758.

[8] Patripassianism is the belief that God the Father suffered the cross with Christ. This belief is also referred to as Modalism, which asserts that the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are simply modes or appearance of God.

[9] Translation of excerpt from Adversus Praxeam Chapter II provided by; http://www.tertullian.org/anf/anf03/anf03-43.htm#P10374_2906966

[10] Translation of excerpt from Adversus Praxeam Chapter II provided by; http://www.tertullian.org/anf/anf03/anf03-43.htm#P10374_2906966

things as materialism, scientific determinism, moral relativism, and agnosticism. Since all of these have grown stronger since his day, it makes sense that G. K. and his arguments may have lost favor over the years.

things as materialism, scientific determinism, moral relativism, and agnosticism. Since all of these have grown stronger since his day, it makes sense that G. K. and his arguments may have lost favor over the years. He also defended Christian ideals like fighting for a Biblical anthropology. A popular topic in London during his time was eugenics. Eugenics proposed the termination or sterilization of people with limited mental capacity. Also, leading thinkers in London had begun to think of the poor as a race of people that had failed to produce good offspring. Chesterton was vehemently opposed to these ideas, writing books, essays, and poems in defense of those who were challenged mentally and economically.

He also defended Christian ideals like fighting for a Biblical anthropology. A popular topic in London during his time was eugenics. Eugenics proposed the termination or sterilization of people with limited mental capacity. Also, leading thinkers in London had begun to think of the poor as a race of people that had failed to produce good offspring. Chesterton was vehemently opposed to these ideas, writing books, essays, and poems in defense of those who were challenged mentally and economically.

When just a child, one thing was always clear to me. “We’re not Catholic.” Then, when I became a Christian at the age of 14, in a small, fundamentalist church, the next layer was added: “Those Catholics are wrong.”

When just a child, one thing was always clear to me. “We’re not Catholic.” Then, when I became a Christian at the age of 14, in a small, fundamentalist church, the next layer was added: “Those Catholics are wrong.”  an orphan’s eyes.

an orphan’s eyes. I also saw something else I don’t see very often. All kinds of people were worshiping together in this downtown gathering. Old and young, from many ethnic groups. Some seemed devout and moved, but not most. Some were obviously very poor. Some seemed totally disinterested. The great equalizer was seen in the queuing up to receive the Eucharist – all those people, regardless of who they have become, and all with different levels of mental ascent as to what was actually happening there … all streaming forward to receive Christ. What they all knew is that they needed this. And the church was there to hand them the tangible Gospel, as Jesus has told us to do. Really, simply, beautiful.

I also saw something else I don’t see very often. All kinds of people were worshiping together in this downtown gathering. Old and young, from many ethnic groups. Some seemed devout and moved, but not most. Some were obviously very poor. Some seemed totally disinterested. The great equalizer was seen in the queuing up to receive the Eucharist – all those people, regardless of who they have become, and all with different levels of mental ascent as to what was actually happening there … all streaming forward to receive Christ. What they all knew is that they needed this. And the church was there to hand them the tangible Gospel, as Jesus has told us to do. Really, simply, beautiful.